The reverse Venn diagram – a tale about political will in Croatia

A comment on my LinkedIn post of my previous blog entry about land titles reform motivated this article about political will in Croatia. The gist of the comment was that there is not enough political will to carry out reforms such as that of land titles registers. This got me thinking and what follows is the result of that process.

The starting point of this analysis is the humble, yet powerful Venn diagram. The point of the Venn diagram is to show where interests intersect, by drawing two or more circles, part of which overlap. In politics, business, and life in general we look for common ground to build relationships. This is illustrated below.

In Croatia, we have a powerful tendency to not find agreement on issues of common interest. A reverse Venn Diagram, if you will. Or a preference to focus on what we do not agree on and to largely ignore that which we have in common. This applies to all walks of life.

Inability to agree on issues of common interest

Elements of this tendency were on display in the public debate about draft legislation governing the rebuilding of Zagreb following the March 22 earthquake.

Not being an independent nation for centuries means Croatia for too long was not in a position make decisions on many important issues. Thus, we have developed a finely tuned tendency to criticise without any skin in the game.

Unfortunately, a large part of our political elites and other stakeholders still behave as if we are in Yugoslavia or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their default position is to oppose agreement rather than seek the best possible agreement. The problem with this approach is that decisions are no longer being made in Belgrade, Vienna or Budapest. We now take all the important decisions in Croatia and criticism for criticism’s sake makes even less sense.

The exception that proves the rule – The Zagreb Earthquake reconstruction legislation

Not having yet adjusted to this reality means too many in society remain blinded to the fact there are very few situations where ideal, unconstrained decisions can be made. Events happen quickly and often while time constraints further complicate decisions. Sometimes, you have no option, but to act. Policy makers do not always have the luxury of considering the quality of potential actions. Some of the criticism surrounding the Zagreb earthquake legislation reflects this blind spot. The earthquake happened, the damage needs to be repaired and there is no time for endless, open-ended ruminations. Nor can we wait for the reform of half of the nation’s institutions. A quick response is necessary, clearly there are gaps, but moving into action can mitigate some of them. I welcome constructive criticism, but I cannot see how waiting, potentially indefinitely, is a better approach.

Also, political parties in power have frequently been criticised for not accepting amendments to legislation tabled by opposition parties. This applies especially to amendments related to the budget. When the final draft legislation for the rebuilding of Zagreb was tabled, the government accepted many amendments from opposition parties. This was an exception, rather than the rule. Generally, in Croatia, people are focussed on their own issues to the detriment of common issues. That is the result of historical experience where many decisions affecting Croatia were made elsewhere without genuine participation in these decisions locally.

The corrosive impact on political will

All of this has a corrosive effect on political will. If we are mainly focussed on the circles of the Venn diagram where there is no intersection, then the benefit of seeking to find common ground narrows. One may well argue that leadership is needed to change this, and one would be right.

That said, as politics is the art of the possible, if most voters continue to debate that which is, by definition, one cannot entirely blame politicians for not resolving issues, or appearing not to want to. Note, I am not saying the lack of political will is not an issue. I am only saying that societal norms, historical experience and inertia can additionally limit its deployment.

Venn Diagrams in reverse and corruption

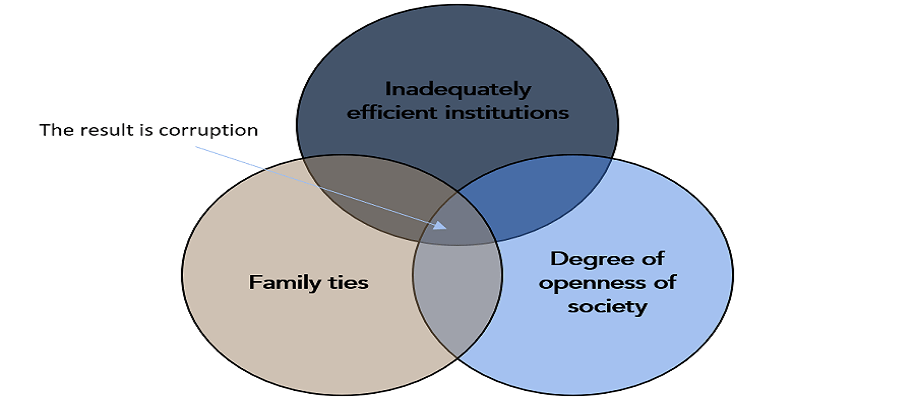

The reverse Venn diagram applies to the issue of corruption. Only in reverse. Here, people focus on the intersecting part of the diagram. The corruption. Yet, people ignore the factors which lead to corruption. For example, the incomplete institutions of state, the family ties prevalent in nations with small populations or the degree of openness of society. Can it really be a surprise when genuine corruption scandals such as the current JANAF case (and the serial leaking of details from investigating bodies) surface? To deal with the intersecting part of the Venn diagram, the individual components need attention. Political will, if you will.

The simplistic approach is to say reform the bureaucracy and court system. But how, if one of this society’s stylised facts is an inability to reach agreement on issues of common interest? What if we are blocked by the reverse Venn diagram?

By no means am I arguing that nothing can be done about corruption or the bureaucracy and court system. Nor that politicians deserve a free pass for not displaying political will. I am only pointing out aspects which make the task specific in Croatia so that we may better design strategies to reform these public services. So that excess political capital is not needlessly expended in dealing with these issues. Because wasting political capital constrains the ability of policy makers and politicians to deploy political will.