Is the Croatian political scene going the way of Slovenia?

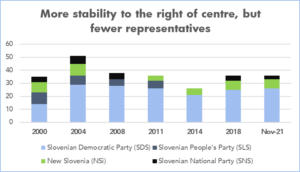

Opinion polls in Slovenia suggest the centre-right (or right wing) government depending on your political persuasion is unpopular ahead of parliamentary elections, due by June 5, 2022. The Slovenian parliament (Državni zbor) has 90 seats and the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS)-led government has only 38 seats, relying on confidence and supply support and picking off independents on a case by case basis.

Slovenia’s fractured parliament…

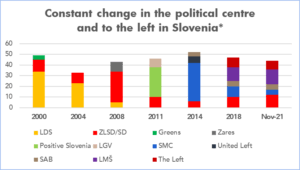

Slovenia’s political scene has been more fractured for some time now. The 2008 general election saw the Social Democrats win 29 seats and the centre right SDS 28 seats. Since independence two core political parties either side of the political centre characterised parliamentary politics and DeSUS, the Pensioners’ Party was an ever present in government too.

By the early election of 2011, tension amongst left of centre parties saw the then Mayor of Ljubljana Zoran Janković form a new party, Positive Slovenia which won most seats (28) in parliament, but failed to form a government, followed by the SDS (26). The Social Democrats had fallen to 10 seats, the Civic List Gregor Virant won 8 deputies, DeSUS ensured it was again represented in parliament with 6 and the People’s Party (6) and New Slovenia (4) contributed a further 10 seats to centre-right parties.

A second early election ensued in 2014, which again mainly resulted from turbulence in left of centre parties. This time the Party of the Modern Centre (SMC) won 36 seats, followed by SDS on 21, DeSUS rose to 10, the Social Democrats fell to 6 (from 29 in 2008), the United Left matched them (only to fall apart in recriminations during the parliamentary term) and New Slovenia contributed 5 deputies to centre right political representation. There was extensive turbulence during that parliament which saw almost as many members switch parties.

…mainly due to left of centre parties

The 2018 elections resulted in an even more fractured parliament, especially amongst centre left and left parties, which in the end saw the SDS, led by Janez Janša, win support in parliament in March 2020 after erstwhile prime minister Marjan Šarec, formerly a member of Janković’s Positive Slovenia, resigned in January 2020. The make-up of Janša’s government looks completely different today compared to March 2020, but he’s still in power.

Since 2008 SDS has consistently won over 20 seats in elections and currently has 26 seats in parliament. The issue is a government need 46 votes to gain a majority. If the two ethnic minority representatives always vote with the government, someone with 26 seats needs at least 18 more to have a majority. Maintaining it is another story, as Slovenia’s history of early elections and intra-election government changes suggests. Not counting the Peterle government from 1990-1992, Šarec’s government was the fifth which did not serve out its full term in Slovenia since independence, a sign of political instability.

Left of centre, 5 parties with a total of 47 seats have not been able to unseat Janša’s government. I guess the combination of a pandemic and Slovenia currently presiding over the Council of the EU changed their calculus. But it still makes one wonder whether with 47 seats after the next election, they would remain together. Or beget another early election as in 2011 and 2014.

Croatia’s multitude of political parties…

Croatia’s political scene is not as fractured, despite the fact the 151 member Sabor spans the entire political spectrum from far left to far right with no less than 22 parties and 12 independents and 5 ethnic minority members (we have already included the 3 SDSS members of the main Serbian ethnic minority party in our tally of 22 parties as they are formally in the government). This patchwork of parties is the result of pre-election coalitions. Banding together increases their chances of passing the 5% threshold for entry into parliament.

The government which formally consists of the HDZ (62) and SDSS (3) plus an independent and one other party (67 seats in parliament) is supported by 10 more votes in parliament including the 5 remaining ethnic minority representatives, so it has a one more vote than it needs to maintain its majority. It is important to bear in mind that ethnic minority participation in government has become a tradition. Irrespective of whether the government of the day is centre-left or centre-right.

…and minimal parliamentary opposition

It is not as if the Social Democrats were in a position after a rather poor performance in 2020 election to put pressure on the government. After early October when the main opposition party, the Social Democrats split into two blocs, that hope is now forlorn. Indeed the 18 dissidents who broke off from the party now have 4 more members than the rump Social Democrats.

Right wing parties which coalesced in the 2020 election campaign under the Homeland Movement coalition which won 16 seats has since split into two groups of 8 and 6 respectively. MOST (The Bridge) also has 8 seats. Most of these representatives were once in the HDZ but personal differences more than ideological issues saw them leave. These parties are also not in a position to threaten the government.

How to form a government of any political flavour in Slovenia?

In Slovenia the challenge is to put together a government of any disposition. SDS roughly gets half the votes needed for a centre-right government, but other similar parties cannot muster enough votes. And we see centre-left options such as SMC (Party of the Modern Centre) then join Janša in March 2020 with 10 seats. Only to leave the government and fall to 5 members in parliament. Apart from generating mistrust amongst other centre-left parties, it has also weakened itself ahead of general elections in 2022.

Source: Republic of Slovenia State Election Commission, IMELUM

* The parties represented in this graph range from centre to centre-left and left according to our classification. The Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia (DeSUS) is an everpresent in parliament and almost every government ranging from 4 to 10 seats and we clasify them as a special interest party

Source: Republic of Slovenia State Election Commission, IMELUM

The story on the left has been one of schism after schism. Liberal Democracy of Slovenia is long gone and the Social Democrats are down to 10 seats from 29 in 2008. This is at least better than the 6 in 2014. There are many transfers during parliamentary terms, further adding to perceptions of instability. We’ll see how the next parliamentary election in Slovenia pans out. Yet, right now, it is difficult to see a stable government forming with support to implement challenging reforms. Slovenia’s growth performance has been excellent since entering the EU. But as its level of wealth converges to the EU average an atomised parliament is not ideal to drive the country’s development.

Croatia’s Social Democrats implode, but president Milanović offers clues of how to credibly respond from the centre left

In Croatia, the challenge even before the Social Democrats imploded was who could credibly present a centre-left alternative to the centre-right HDZ-led option. Namely, the government is nowhere near under as much pressure from the opposition as it would ideally be. Indeed, the only opposition to the government in its first year came from President Milanović (a former Prime Minister and former head of the Social Democrats). As both he and the government agree on further integration of Croatia into EU structures (euro adoption and Schengen entry) as well as on policy toward Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia, his challenge was to demonstrate there was a difference between himself and the Prime Minister. That is one reason why we were treated to regular public slanging matches between the two until earlier this year.

But the pandemic and burnishing his patriotic credentials in articulating more forcefully Croatia’s position vis-a-vis Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia has enabled him to do that. He can then support the government’s restrictions of fuel prices and approach to the pandemic. In a way, he is showing the centre-left how in parliament they can present a credible alternative to the HDZ.

Slovenia is wealthier but less politically stable, Croatia is characterised by more agreement on major issues

Slovenia is generally in a better position. The country is wealthier, more developed and it regional differences are not as pronounced. But it is a politically atomised nation, with many internal contradictions. This means the main political parties need to compromise with numerous smaller parties such as the Pensioners’ Party (DeSUS). This slows or blocks important reforms.

Croatia has one strong pro-European political party and across most political parties a much higher degree of agreement on major issues, from foreign policy to pension reform and the like. Croatia is not without its issues, but is politically more stable.