Migration and Eastern Europe. Is the glass half full?

Image source: Pixabay

Migration is a complex and emotional issue as the impact of the rise in the number of refugees attempting to settle in the European Union since 2015 clearly demonstrates. From the perspective of Eastern European member states, the migration of people from East to West is the longer lasting issue. In this post, we look at Poland and Croatia to show the complexity of migration issues and to argue that perhaps there is room for cautious optimism in Eastern Europe.

Migration has been a hot topic in the EU in particular since the influx of Syrian refugees in 2015, but from the perspective of Eastern European EU member states the outflow which has accelerated since they each joined the EU is the longer lasting issue. From the Baltics to Bulgaria and from Poland to Croatia migration has manifested itself as a major political topic. The new candidate for European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, had to deal with a question on this issue at her first press conference after her nomination.

The European Council meeting at the end of June formally saw the Croatian Prime Minister succeed in ensuring the issue of demography was included in the EU’s strategic plan to 2024. It is of little surprise that the issue of labour migrating West is becoming a point of difference between new and old member states; educating labour takes time and money and when these people have just begun paying back those outlays to society, if they emigrate, another country’s pension and tax system benefits. Any remittances sent back hardly begin to cover the cost of years of investment into every individual.

Economic factors a constant source of motivation for migration

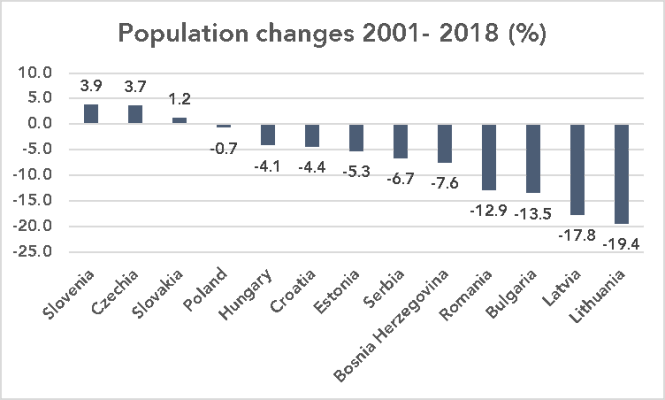

Over the past 150 years emigration from Europe has occurred in waves. Each wave has its own specifics which partly overlap with previous and subsequent episodes, yet economic reasons to move have remained a constant feature. As the graph below shows, over the past 20 or so years, the vast majority of Eastern European states have witnessed a drop in population, sometimes pronounced. Research covering the period of the 1990s despite taking into account the specifics of each country in considering migration, nonetheless, concludes that the issues of unemployment and significant wage differentials between the home country and Western Europe were a constant driver of decisions to move.

Slovenia, Czechia and Slovakia have managed to increase their population over the period covered in the graph, which, given the success of their economies, makes sense. For all the talk of the mythical Polish plumber migrating to the UK and elsewhere, the drop in Poland’s population has been minimal. Of the remaining new member states, one could argue that Hungary, Croatia and Estonia have had some success in limiting population decline given how Romania, Bulgaria, Latvia and Lithuania have fared. That Serbia and Bosnia Herzegovina, the only two non-EU member states in the graph, have seen greater population declines than Croatia does not surprise given their income levels. Their performance does beg the question though, of how pronounced the fall in population would have been had they also joined the EU during the time period covered.

The good, the bad and the unexpected

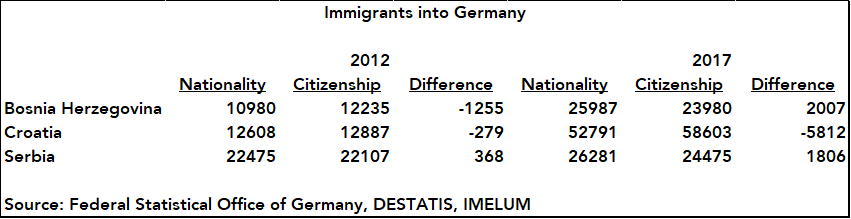

Migration is a complex issue which the cases of Croatia and Poland amply demonstrate. A look at data from Germany (a popular destination for Croatian emigres) uncovers part of the story. In the table below it is evident that in 2012 only 2% of immigrants to Germany with Croatian citizenship declared themselves to be of another nationality. Five years later, with Croatia in the EU by that stage, that share had risen to 10%. Over this same period and in contrast to 2012, there were less immigrants to Germany in 2017 with Bosnian Herzegovinian or Serbian citizenship than individuals who declared themselves as Bosniak or Serbian by nationality. The situation for Croatia in 2017 was the reverse: there were 5,812 more Croatian citizens migrating to Germany than people declaring their nationality as Croatian. Almost two thirds of this difference can be accounted for by the differences outlined for Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia.

Unlike the period after the Homeland War when mainly Croats from Bosnia Herzegovina migrated to Croatia, upon EU accession in 2013, those citizens of the region with Croatian passports also gained more choice in terms of migration options. In that way, not only have Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia lost a part of their potential economic growth as labour forces shrink of the back of migration, but so have neighbouring countries as that loss of growth capacity affects the size of export markets.

In contrast, in Poland we can see how a different set of conditions can impact demographic outcomes. The relatively small drop in population in Poland does not mean that a large number of people have not emigrated from Poland since EU accession. Rather, it suggests that due to the proximity of Ukraine, the relative political instability there and historical ties, Poland has managed to mitigate part of the impact of emigration through immigration from Ukraine and elsewhere in its vicinity.

Data from the Polish Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy indicate that by 2017 almost 200,000 work permits were issued to Ukrainian citizens. In 2013 that number was 20,416. On the other hand, Polish Statistics Office analyses suggest that many of the Poles who did emigrate after 2004 to the EU, have come back, or do so on a temporary basis, circulating between Poland and other EU member states.

Immigration from Ukraine and the circulation of Poles who gather skills, knowledge and capital abroad both support economic growth in Poland. That insight from the Polish data and research I came across in preparing this blog post reminded me of the not insignificant number of times over the past twenty years, I have heard various CEOs from Eastern Europe at conferences and in meetings comment that migration to the West was perfectly fine as long as a sufficient number of those people came back home after a stint abroad.

In recent years there have been signs that Eastern Europeans are gradually making their way back home after gaining experience and saving some capital abroad. With demographic issues now in the EU strategic plan out to 2024 combined with relatively strong economic performance, resulting in wage growth and labour shortages perhaps there is room yet for cautious optimism in Eastern Europe.