Regional Monetary Policy: It’s all about the Exchange Rate

Photo source: Hrvatska narodna banka – Croatian National Bank (CC BY 2.0)

If you studied economics but did not take a course in development economics, then one of the first things that await you in South East Europe is a re-examination of what you learned about monetary policy. Namely, while the standard approach focusses on how the central bank sets interest rates to achieve its monetary policy goals, in a region such as South East Europe where there is a high prevalence of saving in foreign currency (euros mainly), most central banks in the region look to maintain a stable exchange rate in order to achieve their monetary policy goals.

People in the region save in Euros because it has historically been an economically and politically unstable part of Europe. With double-digit annual inflation rates characterising Yugoslavia since 1965, high inflation destroyed the savings of anyone unfortunate enough in the 1970s and 1980s to be saving in the local currency (that is the flip side of the boasts of people lucky and connected enough to have gotten an unindexed dinar housing loan that they paid their loans off for a box of matches). There was one currency redenomination in August 1965 (two zeros were removed) and another in 1990 (four zeros were removed). And unlike today, hard currency was very difficult to come by, even for companies, prior to the reforms of the Marković government in the late 1980s which sought to make the then dinar convertible. The war of independence in Croatia bred a period of hyperinflation, successfully dealt with by the 1994 stabilisation programme, which amongst other things ushered in the currency still in use today. As part of that process a further three zeros were removed from the then Croatian dinar as it was converted to the present currency, the kuna (HRK). The rump Yugoslavia between 1993 and 1994 experienced the second most extreme hyperinflation of all time according to some studies. Indeed, Serbia has only in recent years seen inflation come down on a consistent basis.

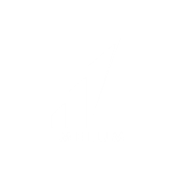

Source: National central banks, IMELUM calculations

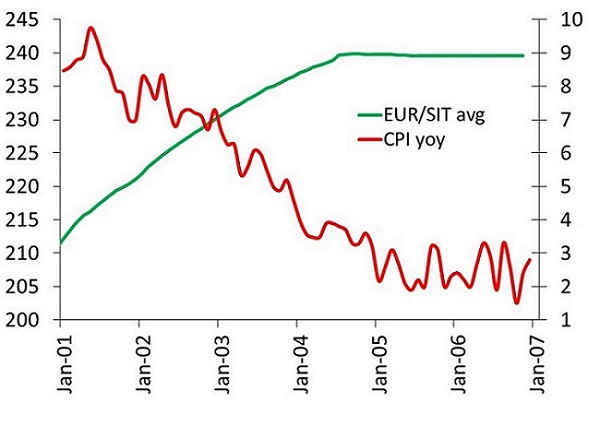

How deep these fears go might best be grasped by the fact almost 40% of Slovenian households saved in Euros even as the country entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 2005 prior to joining the Eurozone in 2007, which meant the currency of the day, the tolar, was fixed at 239.64 to the Euro over this period. Inertia was certainly a factor here, but nonetheless, the fall in euro savings in the total was not extensive. Or that after almost 25 years of currency stability and low inflation in the region’s other EU member state, Croatia, the share of household savings in Euros is over 60%. Memories of financial disaster are long (even though inflation rates in all successor states have been far from the double digits rates which characterised Yugoslavia since at least the mid-1960s) and the most recent financial crisis began only a decade ago. With savings in euros extensive in the region and regulators requiring banks, amongst other things, to match foreign exchange liabilities (savings in FX) and assets in foreign exchange (loans in FX), the prevalence of foreign exchange linked loans in the region is logical. And, as the experience of Serbia during the global financial crisis (see below), or indeed people in the region and wider who borrowed in Swiss francs (CHF) shows, any adverse movement in the exchange rate can significantly constrain disposable income, the ability to service debt or for a business, significantly increase the cost of procuring production materials. Standard economic theory might suggest that a depreciated exchange rate will support the price competitiveness of exports, but the reality of economic conditions in South East Europe suggest otherwise.

Only 15 years after the 1993-94 hyperinflation, in Serbia, extreme macroeconomic imbalances leading up to the financial crisis (e.g. a current account deficit in 2007 of over 20% of GDP) left the authorities with no option but to devalue the dinar (the EUR/RSD moved from 79 at the end of September 2008 to 100 at the end of the year) the share of household savings in foreign currency is over 80%. If you were earning dinars and had a loan linked to euros, that 25% devaluation in the dinar vis-a-vis the euro greatly reduced your disposable income (spare a thought for those citizens of Serbia unfortunate enough to have taken out loans linked to the CHF). That, in a nutshell, is how powerfully the exchange rate can impact on economic conditions. No amount of authorities’ efforts to promote dinarisation (saving in dinars) in Serbia has moved the share of FX savings closer to regional averages.

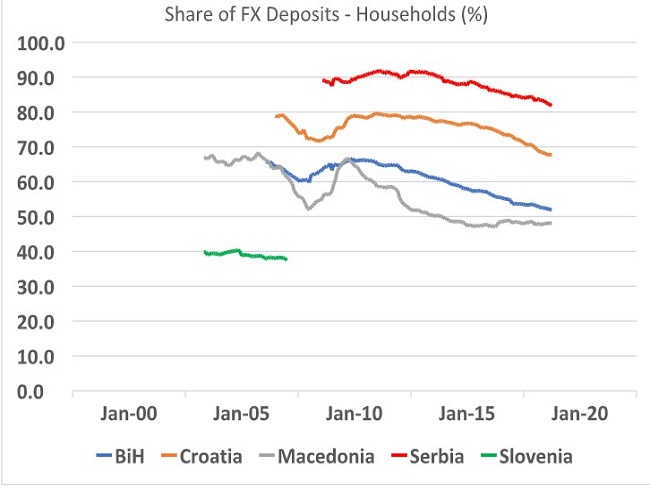

Yet, Serbia is the regional outlier when it comes to monetary policy in the sense that its central bank attaches an explicit importance to the use of a policy interest rate to achieve monetary policy goals. It identifies the first of its five functions as “(t)he National Bank of Serbia manages money and interest rates so as to accomplish a low, stable and predictable inflation rate.” “Safeguarding the value of the national currency” comes second on the list of functions. Much like a central bank in the west, it has monthly monetary policy committee meetings where the policy interest rate is widely debated and changed more often than in Macedonia or Croatia, where it rarely features in official comments on monetary policy settings. Serbia’s central bank regularly publishes extensive inflation reports replete with fan charts of various scenarios and paths to meeting its official target inflation rate. The inflation report is a prominent feature of its communications strategy. As central banks can only target one instrument at a time (the interest rate or the exchange rate) it comes as no surprise that the Serbian dinar exchange rate (EUR/RSD) has been the most volatile in the region. At the same time, inflation has been highest in Serbia over the past decade. I am personally not at all surprised that the recent years of EUR/RSD stability in Serbia have extended the period of low inflation. Elsewhere, where monetary policy has switched to exchange rate stability inflationary pressures came down more quickly. Perhaps Slovenia’s experience up to 2005 and beyond is the most instructive.

Source: National statistical offices, IMELUM calculations

While Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia have independent monetary policies, Slovenia has been in the eurozone since 2007, Montenegro has used the single currency as legal tender since 1998 as has Kosovo since at least independence. Bosnia Herzegovina has had a currency board, like Bulgaria, with the Bosnian Mark (BAM) fixed at 1.95583 to the euro.

The choices of Bosnia Herzegovina, Montenegro and Kosovo are particularly interesting in the context of historical instability, economic and otherwise in this part of Europe. Moving to a currency board (Bosnia Herzegovina’s case) or unilaterally adopting the euro as legal tender (without access to the European Central Bank’s liquidity lines eurozone members enjoy) was still worth it because of the credibility it brought to macroeconomic policy in general. People would anyway save in foreign currency, so why generate additional policy uncertainty by running an independent monetary policy? This way, inflation was brought under control and everyone could credibly conclude that the risk of any political interference in monetary policy was significantly reduced. Also, we are talking about small countries in which policy making and implementation capacities had only begun to be developed with independence. Taking monetary policy out of the equation logically made it easier to direct resources to other policy areas.

Source: Bank of Slovenia, Slovenian Statistical Office (SURS)

With the prevalence of saving in foreign currency extensive in the region, voters have de facto outsourced the setting of base policy interest rates to the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. It is therefore little surprise that in almost all countries in the region local central banks focus on maintaining currency stability, going so far as to implement currency boards or unilaterally introducing the euro as legal tender. As long as households prefer to save in foreign currency in the region, the exchange rate will remain the primary transmission mechanism of monetary policy in South East Europe.